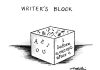

A congenital diaphragmatic hernia, or CDH, is a birth defect where the baby’s diaphragm is not formed completely. The diaphragm, which forms at around 8 weeks of gestation, is a muscle that separates the abdomen and the chest. When there is a hernia in the diaphragm, either from a hole or the complete absence of the diaphragm, organs from the abdomen rise into the chest and negatively affect the growth of the lungs.

Diagnosing a Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

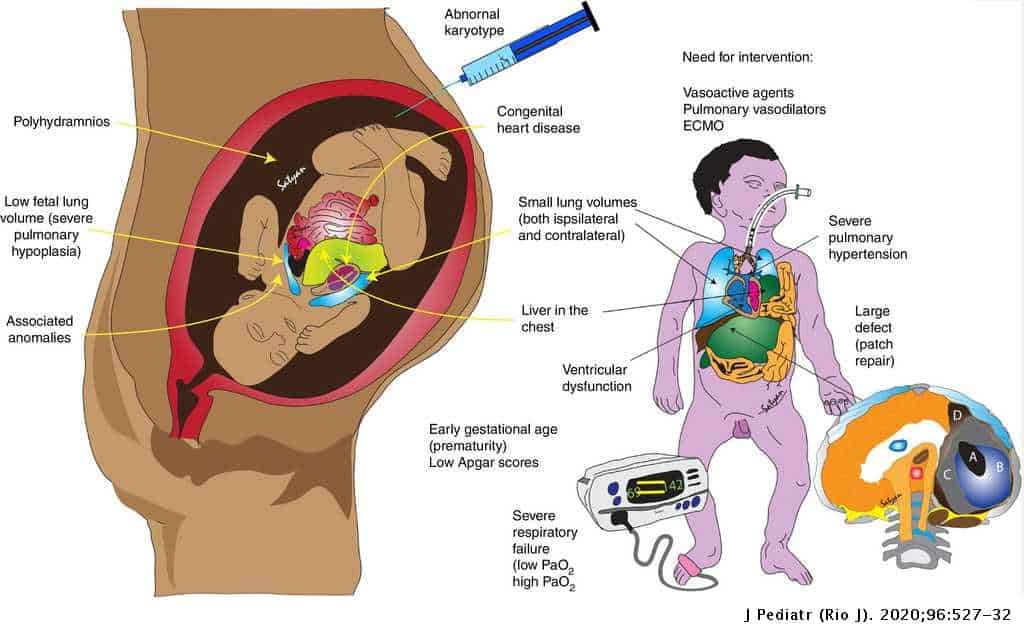

CDH is usually detected during an ultrasound, either from the stomach not being in the correct place or the appearance of bowel (intestines) next to the heart. Further testing is required to confirm the fetus’s CDH and its severity, and may include a fetal MRI and an echocardiogram.

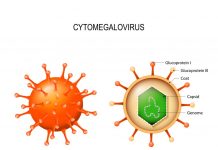

Diaphragmatic hernias are usually accompanied by other associated anomalies; genetic tests, such as a chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or an amniocentesis, are recommended to find any possible chromosomal abnormalities that may affect the baby’s survival rate.

Survival Rate Factors for Babies With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

The severity of the CDH affects the fetus’s rate of survival in the following ways:

- The position of the baby’s liver is an important indication of how severe the diaphragmatic hernia is. “Liver down” is good: This term is used to say that the liver is in its correct place – the abdomen. “Liver up” is more severe, and indicates that at least a portion of the liver has herniated into the chest.

- The LHR, or lung-to-head ratio, is calculated during ultrasounds and is used to estimate the size of the fetus’s lungs. If a baby has an LHR over 1.0, she has a good chance at survival.

Other factors that must be considered when discussing a fetus’s survival rate is whether there are any associated abnormalities, such as heart defects and neurological defects like anencephaly and spina bifida. Some chromosomal abnormalities that have been found in CDH babies are trisomy 13, 18 and 21. CDH has also been associated with Cornelia de Lange syndrome and Fryns syndrome. The presence of any of these should be taken into account when determining the survival rate of a baby diagnosed with diaphragmatic hernia.

Long-Term Effects of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

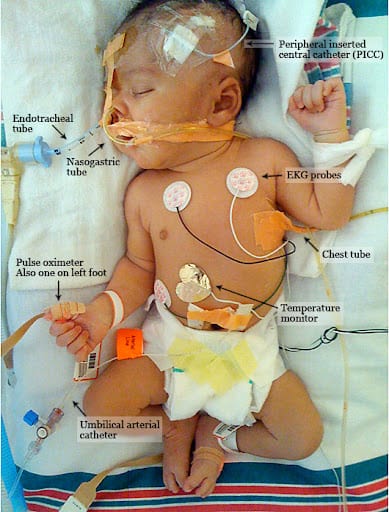

All babies who survive a congenital diaphragmatic hernia will have pulmonary hypoplasia, which is the term for when lungs fail to develop completely. While some babies are able to breathe on their own after being weaned off ventilation at the hospital, others may develop chronic lung disease and will therefore need oxygen and medications after they have gone home.

Many babies who have had their stomachs or bowels herniated during gestation develop gastroesophageal reflux (GER), which is where acid rises into the esophagus, causing heartburn and vomiting. If feeding or breathing problems arise due to acid reflux, the baby is considered to have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Medications are a typical treatment for GER and GERD, but if symptoms persist or worsen, a surgery called fundoplication may be performed to stop the acid reflux.

Whether a CDH survivor has pulmonary hypoplasia, GER, or both, she is likely to display poor growth. Babies with smaller lungs have to work harder to breathe; during feedings, a CDH baby is likely to take frequent breathing breaks and tire more easily than a normal baby. She may require extra nutrition and calories through a feeding tube. Acid reflux can exacerbate the situation, causing oral aversion and a refusal to feed due to pain in the esophagus.

Skeletal problems may occur as a result of CDH. Scoliosis, or a curved spine, is one such possibility due to the uneven nature of the baby’s chest. Often infant scoliosis will correct itself; however, if a curved spine is detected, periodic x-rays may be taken to monitor the spine’s curvature. The other skeletal problem is a pectus excavatum, or a depression in the breastbone. There is little health risk associated with this deformity, but if the depression were to become severe, could lead to heart and lung impairments.

Other problems that may affect CDH survivors are hearing loss, seizures, and developmental delays. There is also the chance of reherniation, which is more common among survivors with diaphragmatic hernias large enough to require the use of a patch during repair.

Quality of Life for CDH Survivors

While health is an ongoing issue for the first few years of life for a survivor of CDH, many survivors eventually overcome or outgrow their health problems to become happy, healthy children. With continued research and increased awareness of congenital diaphragmatic hernia, medical care for CDH patients is bound to improve, thus increasing survival rates and the resulting quality of life for survivors.