International Relations (IR) is most commonly categorized as a sub-field of Political Science. In simple terms, IR scholars seek explanations for why actors in international politics behave the way they do, and what factors influence and motivate their behaviour.

It is important to note that although the nation-state continues to be the most important actor in international politics, most analysts who study IR at least recognize the growing importance of other actors.

These include inter-governmental organizations, such as the UN and the EU, and of non-governmental organizations, including trans-national advocacy groups like Amnesty International and trans-national corporations.

Within IR, the fundamental debate between academics revolves not only around what these explanations are, but also how (if at all) they can be reached.

The ontological and epistemological beliefs held by such analysts generally leads their ideas to fall within one of IR’s three major theoretical paradigms.

Realism

Since the study of IR took off after World War II, realism has been its dominant paradigm. Although there are several sub-categories amongst self-described realists, these analysts are bound together by the common assumptions they hold with respect to human nature and the international politics.

Generally speaking, realists are positivists. They believe that objective laws govern both the natural and the political world. It is possible to discover these laws using a combination of history, observation, and scientific methods.

According to realists, the way political entities (ranging from ancient tribes to modern nation-states) have interacted with one another has remained fundamentally unchanged since the dawn of history. All political groups are first and foremost concerned with their own security.

They will invariably put their interests above those of other groups. As one can imagine, this situation often leads to conflict between different groups operating within the same system.

From a realist perspective, nation-states are the only true vehicles of political power, and therefore are far and away the most important units of analysis in the study of IR. States exist as independent entities in an anarchic system; that is to say, there is no “government of governments” which can be relied upon to check the power of the sovereign state.

Realists do not deny the possibility for co-operation between states, but they maintain that the long-term tendency of states in such an environment is towards competition. States always must be wary of other states’ intentions. State security is a zero-sum game, and if state leaders fail to acknowledge this, they do so at their own peril.

Modern realists claim to be the intellectual descendants of many prominent historical and political philosophers dating as far back as the Greek historian Thucydides. Such important figures include Sun Tzu, Niccolo Machiavelli, and Thomas Hobbes.

Liberalism

Like realists, liberals in IR sub-categorize themselves in several ways, but they are bound together by a number of core beliefs. Generally speaking, liberals too see the world in positivist terms.

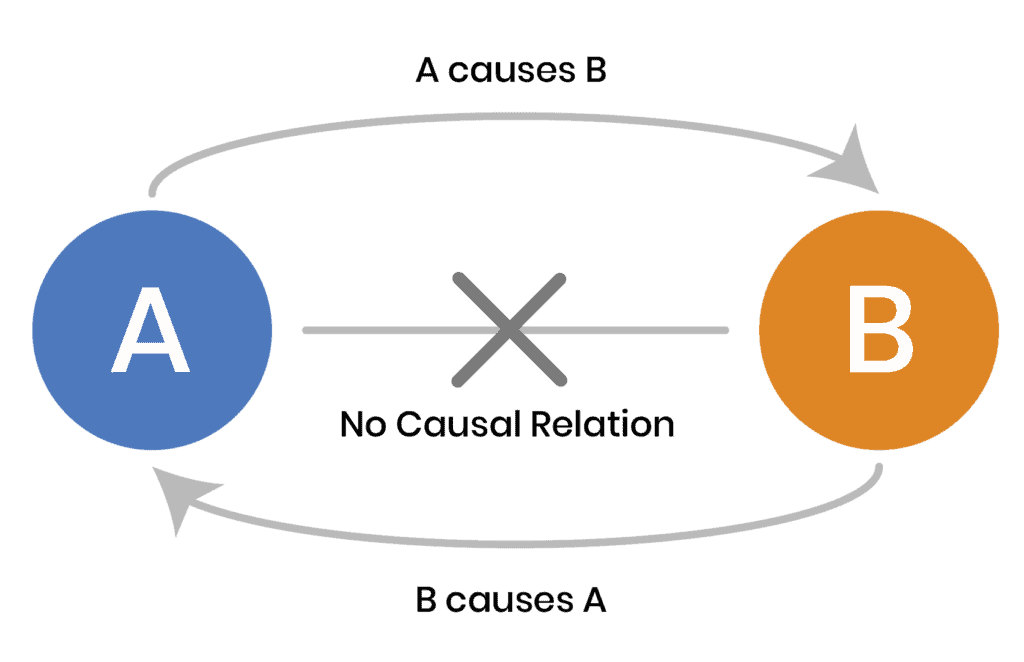

Liberals differ from realists in what they see as factors that can influence state behaviour at the international level. Realists see a state’s material capabilities (population, resources, military strength) as determining its actions at the international level.

Liberals do not dispute the importance of such capabilities, but they deny that a causal relationship exists between the two. For liberals, alternative factors such as the political culture of a state, its economic system, or its regime/government type, can impact its behaviour.

The second major difference between liberals and realists is that while liberals recognize that the international system is anarchic, they do not see this fact alone as grounds to claim that the system is naturally conflictual. This is because liberals believe in the possibility of absolute gains, as opposed to the zero-sum mentality of realists.

In other words, for liberals, it is possible for states to gain power and influence in ways that do not threaten the security of other states.

Needless to say, in today’s world, liberals are generally more optimistic about a peaceful future than realists are. They emphasize the role of inter-governmental institutions in helping increase cordial exchange between states, and allowing countries to pursue their national interests in open and non-threatening ways.

Many liberals contend that over the last several decades some of these inter-governmental institutions have even managed to supersede the authority of the state. The World Trade Organization, for example, can overrule a national policy if it conflicts with trade policies that have been agreed upon by its members.

For liberals, cultural and economic globalization are positive phenomena. The ability of information, ideas, and culture to permeate national borders encourages mutual understanding and facilitates the idea of a “global community.” In terms of economics, free trade and open markets creates interdependence between states, which in turn serves to reduce the likelihood of international conflict.

Finally, most liberals draw attention to the spread of democratic ideals in the last several decades, and they emphasize data showing that democracies rarely (if ever) go to war with one another. Since citizens primarily bear the costs of war (loss of life, destruction of property, increased taxation etc.), liberals believe that under a democratic regime, they are less likely to elect or accept leaders that are inclined towards it.

The liberal tradition in IR has its roots in European liberal philosophy. Liberals today claim figures like Immanuel Kant as their intellectual forefathers.

Constructivism (or Social Constructivism)

Constructivism is the most diverse of the major IR paradigms, and it is consequently the most difficult to summarize. It is perhaps easiest to begin explaining what constructivism is by explaining what it is not; that is, a theory with a positivist ontology.

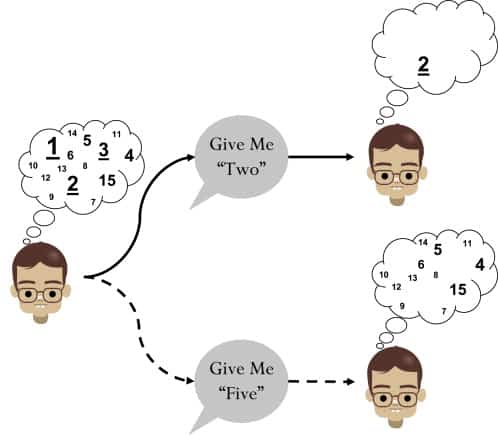

Constructivists, generally speaking, are post-positivists; they reject the notion that we can come to “know” the social and political through the methodological approaches used by the natural sciences. When explaining the relationships between states and other actors functioning at the international level, there are no objective laws for constructivists. Explanations instead must come from analyzing the social constructions of both the actors and the structure (re: the world) in which they operate.

Constructivists make the claim that both realists and liberals drastically underestimate the importance of ideas and norms in international relations. This fundamental disagreement between constructivists and others is known in IR circles as the “rationalist – constructivist” debate.

The following is an example of a situation in international politics from a constructivist perspective.

Throughout the majority of world history, states have normally kept territory they have conquered in war. The desire for states to expand their territory, in fact, has been noted by John Vasquez to be the most common reason political entities have gone to war in the first place. The right of the victorious state to keep territory acquired in war was implicitly recognized by the defeated state, for they would have taken the same actions had they had won.

Nowadays, however, wars fought for the purpose of territorial expansion have become increasingly rare. According to Mark Zacher, this is large part because of the development of the “Territorial Integrity Norm,” that is, a general understanding and acceptance amongst states that forceful territorial aggrandizement is unacceptable.

- What Is Aromatherapy Vs. What Are Essential Oils?

- What is La Tomatina in Bunol, Spain Like? What to Expect at the Famous Tomato Throwing Festival

Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, for example, was condemned by the UN Security Council and met with a strong multilateral response. According to constructivists, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 is not an attempt for the US to increase its territory, but rather to use the “war on terror” to facilitate the growth of a global norm in which states agree to denounce terrorism by non-state actors (such as Al Qaida).

Conclusion

This by no means a complete summary of IR theory or a sufficient explanation of all the debates within the field. It is, however, what it is: a crash course in basic IR theory. I haven’t gone too far into the criticisms of the different paradigms, but I’m sure you can find the positives and negatives of using either of them.