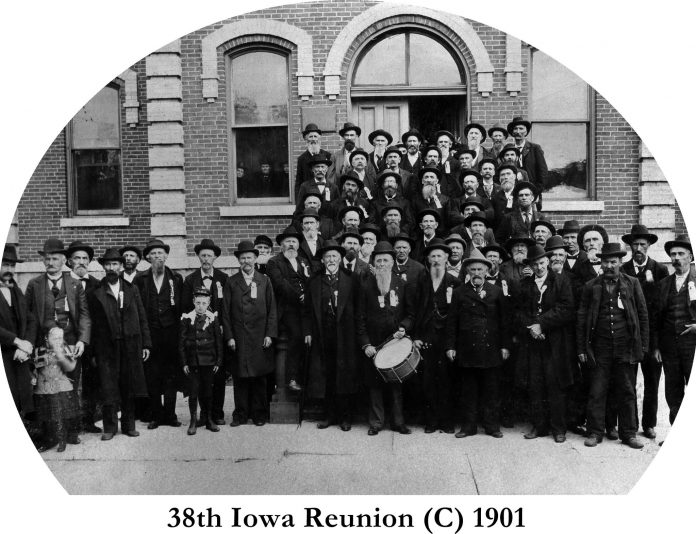

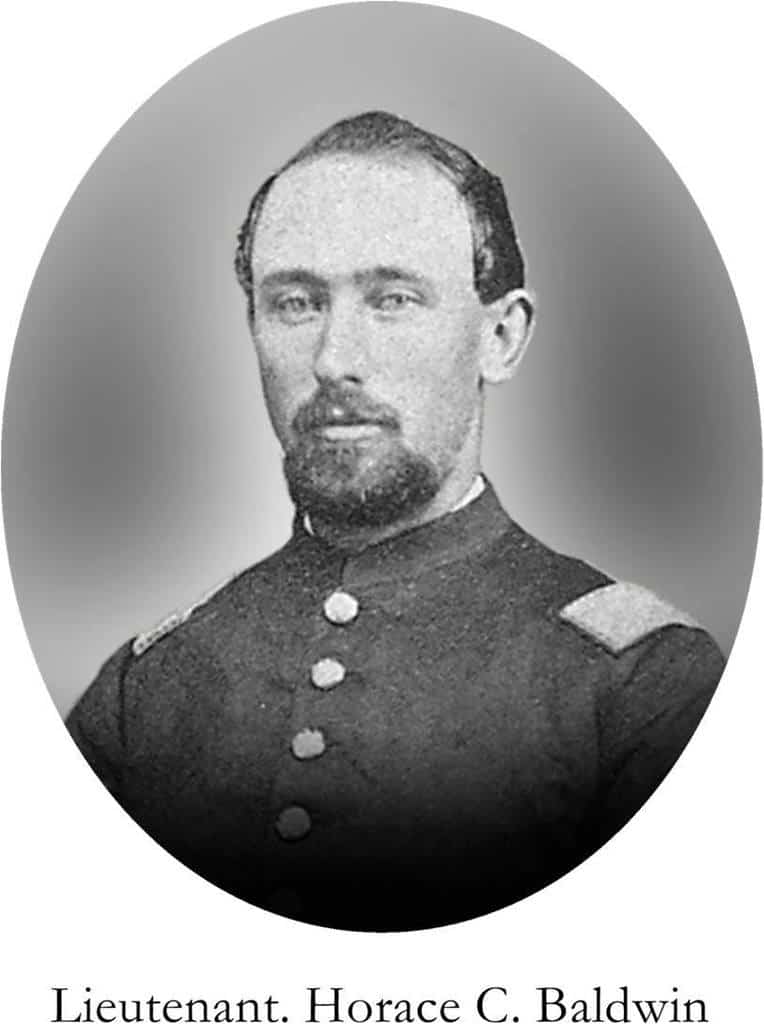

While the 38th Iowa Infantry helped the Union army besiege and capture Vicksburg, MS in 1863, the regiment was itself besieged by disease.

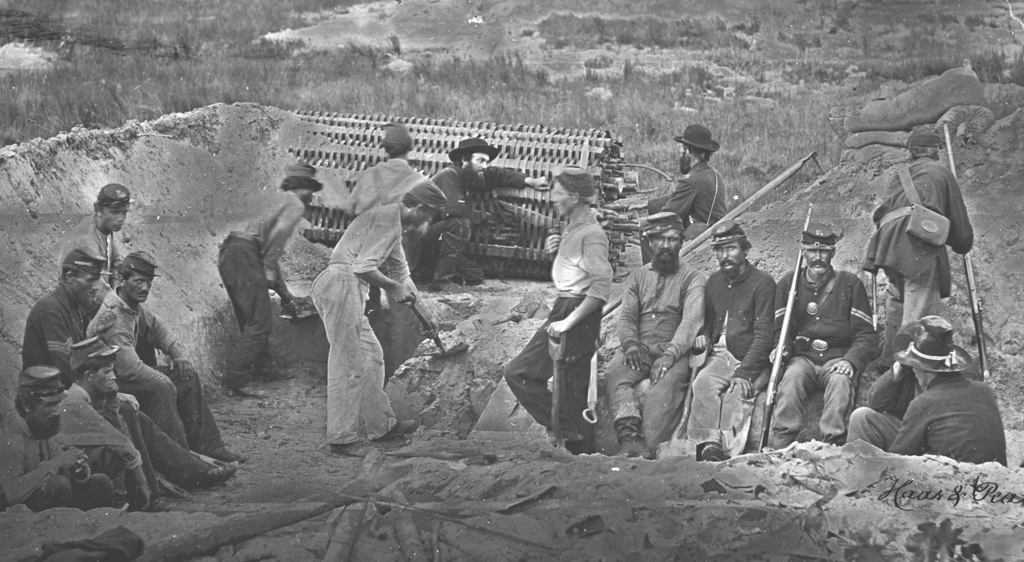

On June 15th, 1863, the 38th Iowa Infantry regiment, over 900 strong, was ordered to extend the extreme left of the Union siege lines south of Vicksburg. Hugging the Mississippi River and mosquito infested swamps to their left, they made camp between a grove of cypress trees and high bluffs.

Unfortunately, there was no air circulation and the sun reflected off the white bluffs, beating down on the soldiers.

Malaria, Typhoid, and Dysentery

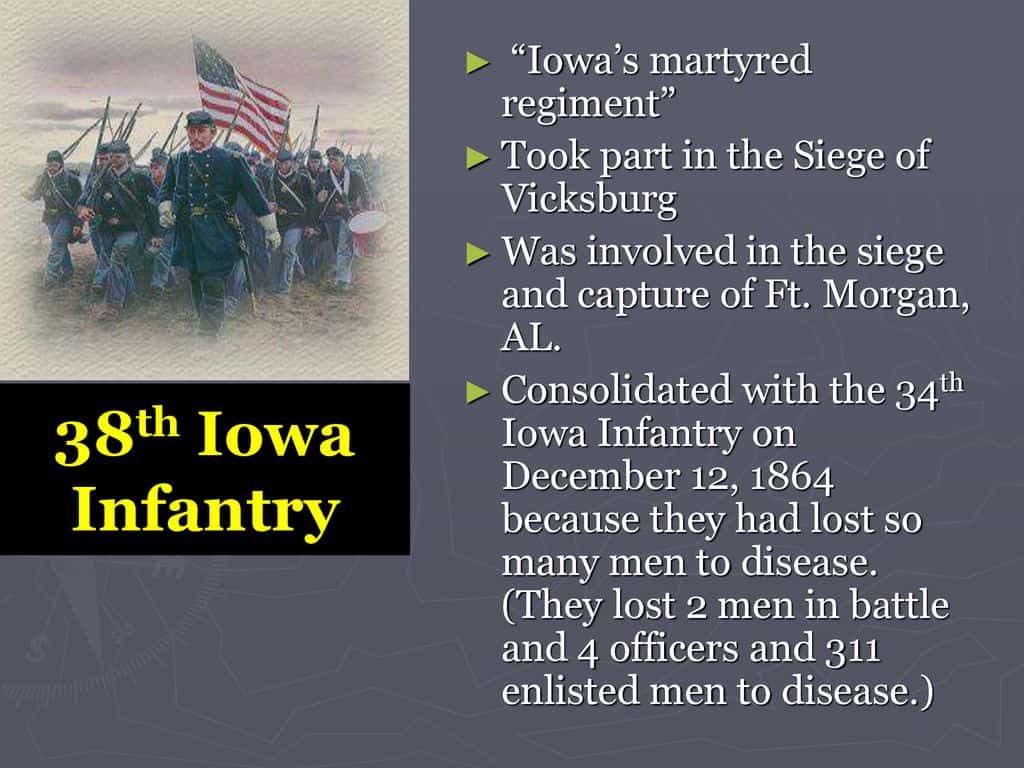

From then to early July, the regiment was busily engaged, under an oppressive sun, mounting guns, digging trenches and rifle pits, and being on picket duty. On June 24th, Captain Horace Baldwin of Company C claimed that over 200 men were too sick for duty.

Men were also getting little sleep because of their arduous duties and insects, “the mosquitos are the worst for they will not let a fellow sleep,” complained Baldwin.

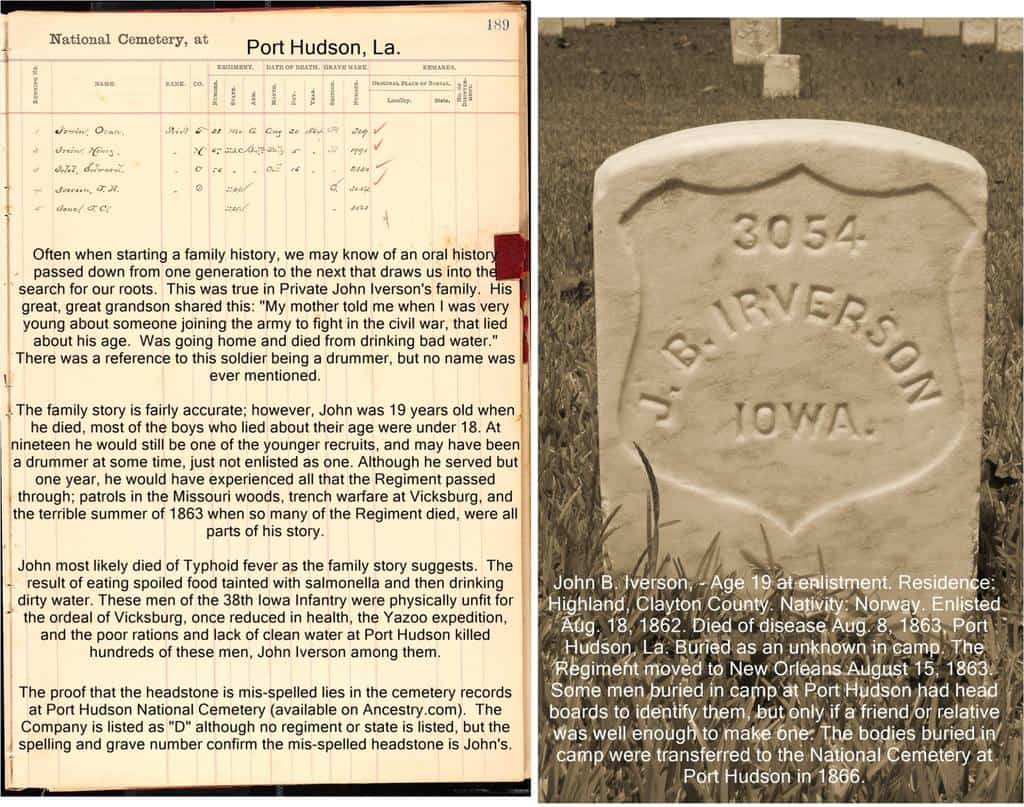

Malaria acquired from the mosquitos, and typhoid and dysentery resulting from unsanitary conditions tempered the celebrations for the 38th after Union forces captured Vicksburg on July 4th. Private Jacob Kerian possibly died of malaria. He would have had shivers down his back, feeling cold while his temperature rose to around 105 degrees (F). In addition, he might have had a splitting headache, nausea, and vomitting.

After a deep sleep, he could have broke into a profuse sweat and had fevers every couple of days. Finally, after doses of whiskey and quinine, the common elixirs for the disease during the war, Jacob’s liver failed and he died July 8th.

Port Hudson

The 38th’s exertions continued. In mid July, they were ordered to march north to Yazoo City where they captured supplies. Then, after a severe march towards Jackson, Ms, in which they experienced terrible heat and the lack of water, they were summoned back to Vicksburg and shipped south to defend Port Hudson, La. The regiment left 250 sick men behind in Vicksburg hospitals.

By August 2nd, only less than 150 men in the regiment were fit for duty. Baldwin described the gloomy scene, “men dying around with disease from three to four every day and to see these poor fellows lying scattered about under their little tents with the sun pouring down upon them has been enough to make the stoutest of hearts sink with despair…” At its low point, the 38th on August 13th had eight officers and twenty men able for duty.

As the gloomy situation persisted, the anger of the 38th for their division commander, Francis Herron, simmered. “It is wicked for our General Herron to keep us here when they know that by sending us north they could save many lives…You may best assume that he has few friends in the 38th Iowa,” Baldwin lashed out.

Convalescence

Finally, the regiment was sent to a convalescent camp at Carrollton, La. It was a shady place with vegetables and access to ice. Iowans back home, including governor Samuel Kirkwood, heard of their plight and sent a sanitary agent with supplies to Carrollton. By mid October, the regiment was ready for the field with over 300 men, a shadow of its former self.

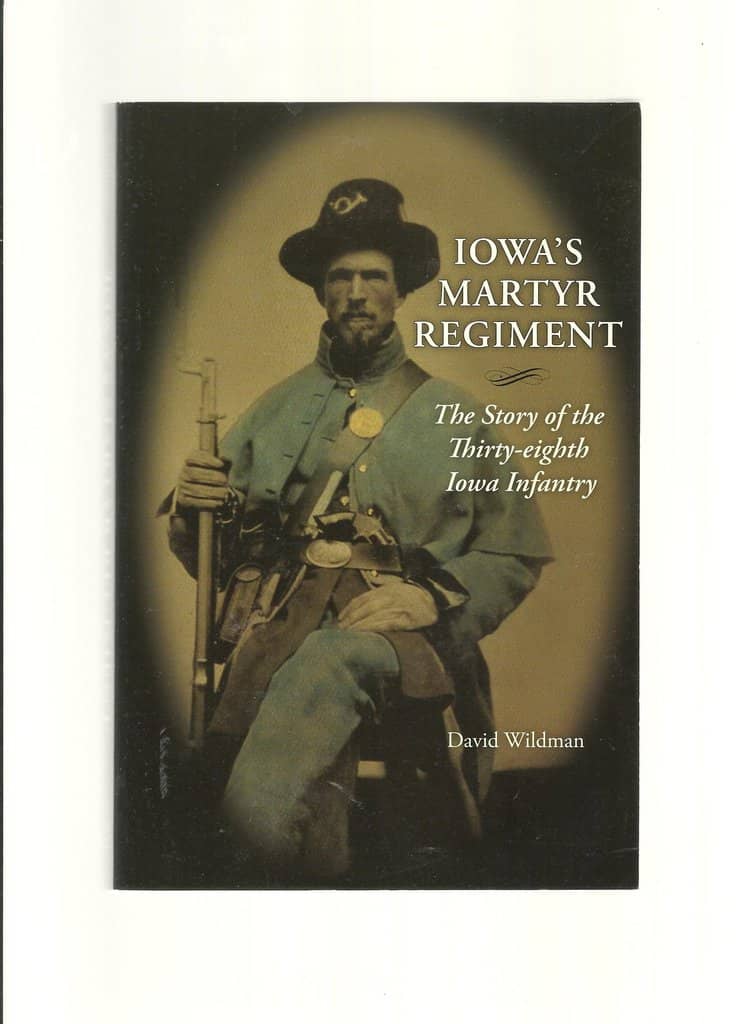

By the end of the war, 311 men and officers died of disease in the 38th, with 130 discharged, most of those due to illness. Amazingly, only one died in battle and one died of wounds. What the 38th suffered at Vicksburg and Port Hudson earned them the title of “Iowa’s Martyr Regiment.”