The concept of Britain as a unified nation truly came into being with the signing of the union act in 1707. A combination of the fractious nations of England and Scotland, common ground was needed in order to ensure the new union’s survival. The reticent attitude amongst the general populace towards the Union Act, particularly in Scotland, was negated slightly by the presence of Queen Anne, the monarch, last of the Scottish House of Stuart.

The Monarchy

Ignoring the rather inaccurate “stiff upper lip” stereotypes, it is difficult to find character traits common to the people of Britain. If there is anything acting as a gravitational force, pulling the disparate peoples of this island together, then nothing embodies ‘Britishness’ to such an extent its great institutions, most notably the monarchy. Originally standing at the zenith of the British class system – a throwback to the feudal ages – the monarchy, now stripped of all but superficial powers, has become a national institution with which foreigners and Brits alike can identify.

The British national anthem itself demonstrates the regard with which the monarchy is held within the country. Whilst ‘Star Spangled Banner’ eulogises over America’s flag, La Marseillaise calls its citizens to the defence of France and Fratelli d’Italia to Italy’s, Britain is almost unique in that its national anthem sings praises to its monarch. Traditional British conservatism is evident here as the anthem looks to the Queen to sate the craving for order that has been ever present in British society, evidenced in the lyric ‘long to rule o’er us’. The plea offered to God witnesses the introduction of another key institution in early British society, the Protestant Church.

Protestantism and the European Superpowers

Henry XIII famously created the Church of England through pursuit of self-interest: a divorce from Catherine of Aragon, an unprecedented matter in the Catholic Church, to marry Anne Boleyn. Nearly 200 years later, this selfishness on the part of King Henry had resulted in a powerful independent Church within Britain whose large influence promoted increased commitment to the Monarchy – due to the monarch’s unique position as head of state and head of the Church of England – as well as providing Britain with a common enemy: Catholicism. Such intolerance towards Catholicism resulted in increased anti-European sentiment within the country, with the majority of Western Europe, including France and Spain being followers of the Pope in Rome. As a result, numerous religious wars raged, perhaps the most famous of which was the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Wars with Europe have always increased a sense of national spirit and camaraderie at home; even if people do not know for what cause they are fighting for, the mere fact that they are fighting for their country augments their sense of belonging through shared experience. This was particularly evident in the Napoleonic Wars with huge national pride in the achievements of the Royal Navy. Victories for the Navy inevitably succeeded in the proliferation of that typically British idiosyncrasy: a (mostly misplaced) sense of national superiority, a trait that would only gain momentum with the enlargement of the British Empire.

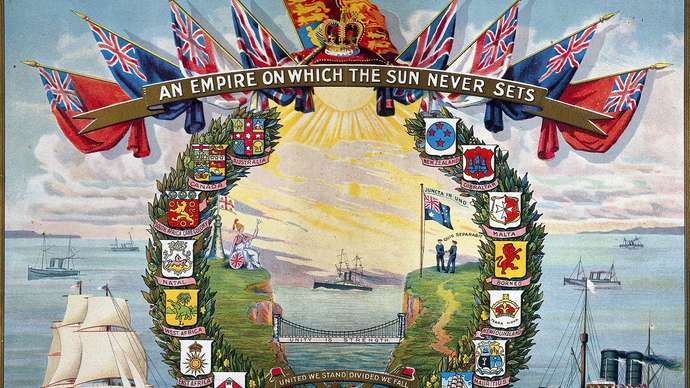

Empire

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Britain’s largely successful attempt to seize control of as much of the world’s resources as it could – using the guise of ‘civilizing’ other countries – cemented the foreign stereotype of the British as arrogant colonials for decades to come. As Britain prospered under the inevitable wave of free market capitalism that the Empire wrought, it was hard for its citizens not to feel a sense of superiority to their backward and oppressed subjects.

The British Empire was – and still is – however, a huge source of national pride, in many respects defining Britain today in terms of the sentiment and nostalgia shown towards the great institutions that were formed out of the Act of Union. These great institutions, which have stood the test of time, are a unique facet of ‘Britishness’ in the way that they have shaped society – a facet more central to ‘Britishness’ than any overriding character attribute.