As the presidential campaign begins, voters may be looking for insights into the make up of the various candidates in an attempt to answer questions about how the person might perform once in office. Many scholarly studies have been undertaken in an attempt to help voters predict how candidates for public office, the presidency in particular, will behave or perform if elected.

A great many of these studies end up as not much more than thought experiments in undergraduate and graduate classes or games at academic cocktail parties. Some such studies were never intended for much else other than after the fact categorization of presidents. Can these scholarly works actually help the average voter in his or her search for answers about the candidates asking for their votes?

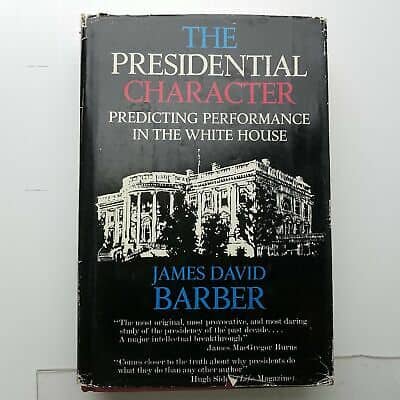

Voters would certainly love to know which candidate might be more likely to wind up in a scandal or be ineffective in responding to a crisis, but unfortunately most voters are not soothsayers. Among the most ambitious attempts at prediction and simplification of prediction is work by James David Barber. Made famous outside of political science by his 1969 prediction of the behavior Nixon would exhibit if immersed in scandal, Barber has also suffered great criticism for his research methods and for making future use of his categorizations difficult.

The latter concern arose as potential presidential candidates became familiar with his work and made every attempt to appear as though they belonged in the category of character Barber had said was best suited to be president.

Four categories of character, according to Barber

Barber, who on the eve of Nixon’s inauguration and again still early in his first term, had argued that if faced with a scandal Nixon would deny any wrong doing, blame others, and retreat, postulated that presidents and presidential candidates could be measured on two dimensions: activity (how engaged they were in politics) and affect (how they felt about politics and their job).

Activity would be measured in terms of two categories – active or passive – and affect the same, but using positive or negative as categories. Crossing the two dimensions created a 2 x 2 matrix and four categories of presidential character: Active/Positive, Active/Negative, Passive/Positive, and Passive/Negative.

The Active/Positive type, argues Barber, is the best character type to have serving as president. This individual is self-confident, learns from his or her mistakes, works at the job, and just generally enjoys politics and the use of power to achieve good things. Presidents who fit into this type are Teddy Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, and John Kennedy.

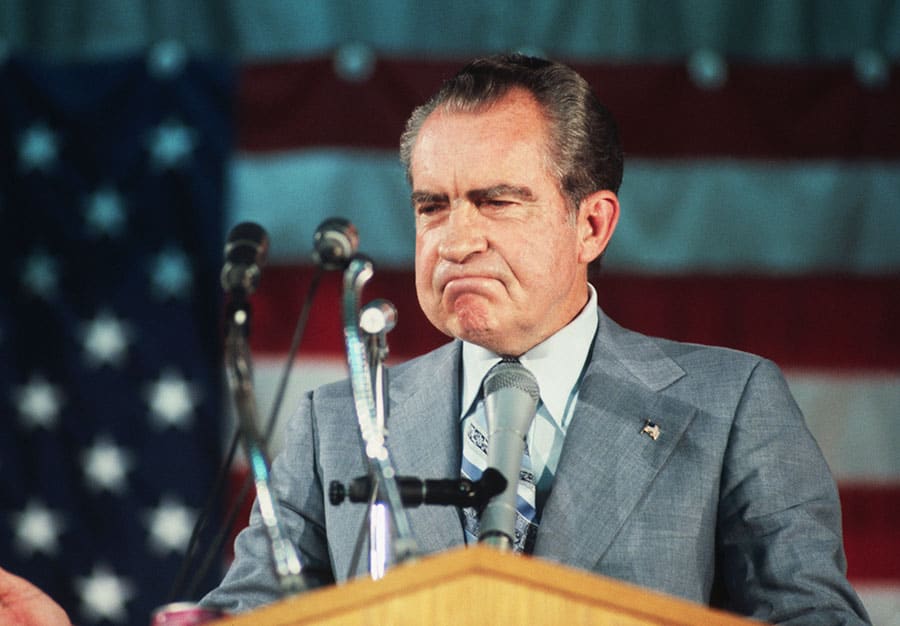

The Active/Negative type is the worst character type to elect president. Individuals in this category suffer from low self esteem and get no enjoyment out of the job. Their higher levels of activity may be a mechanism by which they cover up their lack of confidence. For Barber, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon were the archetypes of the Active/Negative character.

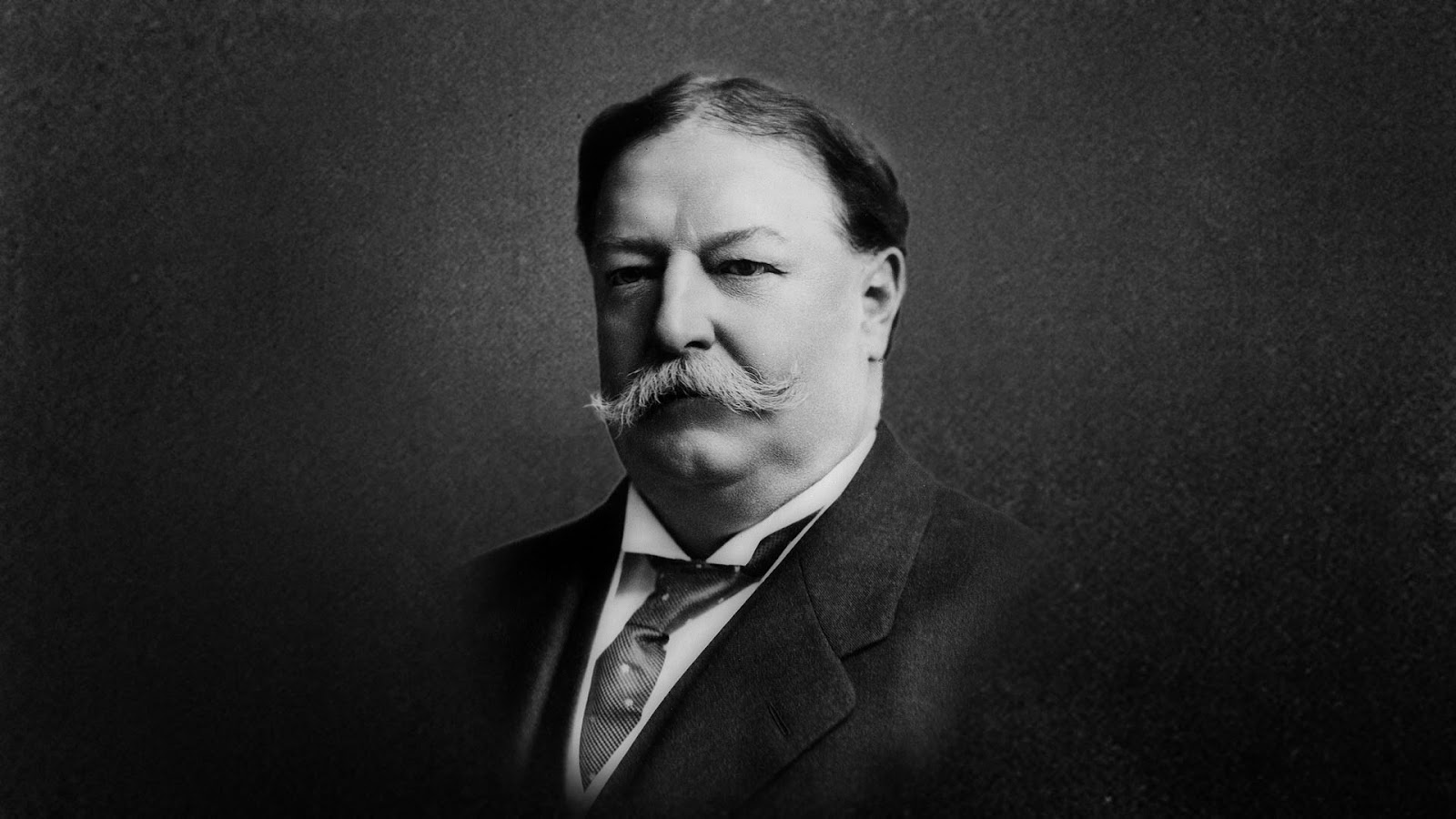

Seemingly agreeable and cooperative, the Passive/Positive individual also suffers from low self esteem and may compensate with “superficial optimism.” These outward characteristics are what can make these individuals successful in politics – they attract voters. The example Barber gives of this type is William Howard Taft.

Lastly, the Passive/Negative type is withdrawn and also has low self esteem. Individuals of this type – Barber suggests Dwight Eisenhower – see politics as service.

The problem with this system of categorization is that it is difficult to do the necessary research, called psycho-biography. If it is difficult for social scientists to do this research well, the average voter will have a nearly insurmountable task. Barber has also been criticised for “cherry picking” the information in each president’s biography that proves his selection of the president for a specific category and that, perhaps he went about his task with something of a partisan bias. Still, we can find something useful in his work.

Other attempts

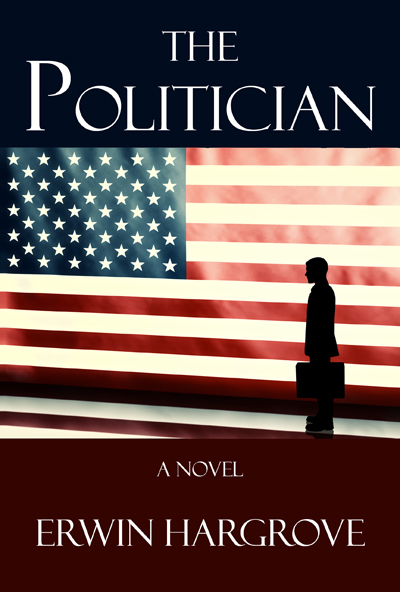

Political scientist Erwin Hargrove has both praised and criticized Barber for his contribution. His praise focused on the clarity of presentation and the fact that Barber had used language that made psychological concepts more usable for those who were not trained in psychology.

Going even further from the psychological examination of character, Hargrove, along with co-author Michael Nelson, created another 2 x 2 matrix that has less to do with the person than with the conditions under which the person is president. They ask two questions. First, is the presidency weak or strong? Second, Is this condition good or bad for the country? To describe the four types of presidents that result from the intersection of these two questions, Hargrove and Nelson use Biblical references.

The Savior is the type of presidency that occurs when the both the institution is strong and that strength is good for the country. This was they case for the Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, and early Johnson presidencies.

The Satan occurs when the institution is strong and this condition is bad for the country, or the period during the latter portion of the Johnson Administration and the Nixon Administration.

The Samson occurs when the institution is weak and that weakness comes at a bad time for the country. Hargrove and Nelson argue that this was the case during the terms of Ford and Carter. They argue that this condition is also likely to occur when other institutions are also weak and do not have the capacity to fill the leadership void.

The Seraph occurs when the institution is weak and that weakness is good for the country, such as during the Eisenhower Administration.

Note that Hargrove and Nelson abandon evaluations of the individual and look to the institution instead. Certainly, the individual who sits in the office has something to do with the relative strength or weakness of the office, but this analysis leaves out a good bit of the consideration of the traits of the individual.

Other political scientists (historians and psychologists as well) have taken stabs at trying to explain or predict the behavior of presidents in the Oval Office based on some perceived or observed pattern of behavior. Some of these attempts get a bit more complex and end up suffering from the very symptom Barber sought to avoid – heavy reliance on psychology. There have been some interesting attempts at post-hoc psychoanalysis of presidents and attempts to link forms of mental illness to good leadership qualities.

Conclusion

So, what should we look for in candidates then? Naturally, candidates will tend to hide their weaknesses or instances in their background that might demonstrate character flaws. Watch for the reasons they seem to be running.

Do they exhibit extreme behaviors like seeming to be always angry or overly optimistic? Or, do they seem balanced? Do they have a history of not coming clean about any shortcomings they may have, an inability to admit to mistakes, or a string of “innocent” misbehaviors? If they change their positions does, it seem to come from a true epiphany or conversion, or is it simply flip-flopping? Do they seem to be able to grasp the kinds of details it might be important for someone holding the office to have?

As long as we continue our fascination with individuals who occupy or seek to occupy the office of president, social scientists will seek to find a way to explain their individualized behavior. Presidents who occupy the office leave an indelible mark on the institution and our political system and we are right to try to find ways to make better choices. While most of the attempts described or alluded to here fall somewhat short of the mark, each attempt takes us that much closer to knowing which candidate will perform better once in office. Short of forcing candidates to submit to a public session on the couch with a psycho-analyst, the grueling process of going before the media and the public will have to suffice.