Culture shock is the name given to the state of disorientation that results from exposure to an unfamiliar culture. (Repatriating expats are affected by a variant known as reverse culture shock.) Its symptoms are both physical and psychosocial.

Culture shock affects expatriates in two ways:

Interpersonally, it negatively affects the expat’s perceptions of the new culture and its people. It also indirectly affects the reactions of host country nationals toward the expat (for example, when the expat’s usual behaviours are unacceptable in the new culture.)

Intrapersonally, it negatively affects the expat’s self-perception, when an inability to function effectively in the new environment leads to an identity crisis fuelled by self-doubt and uncertainty.

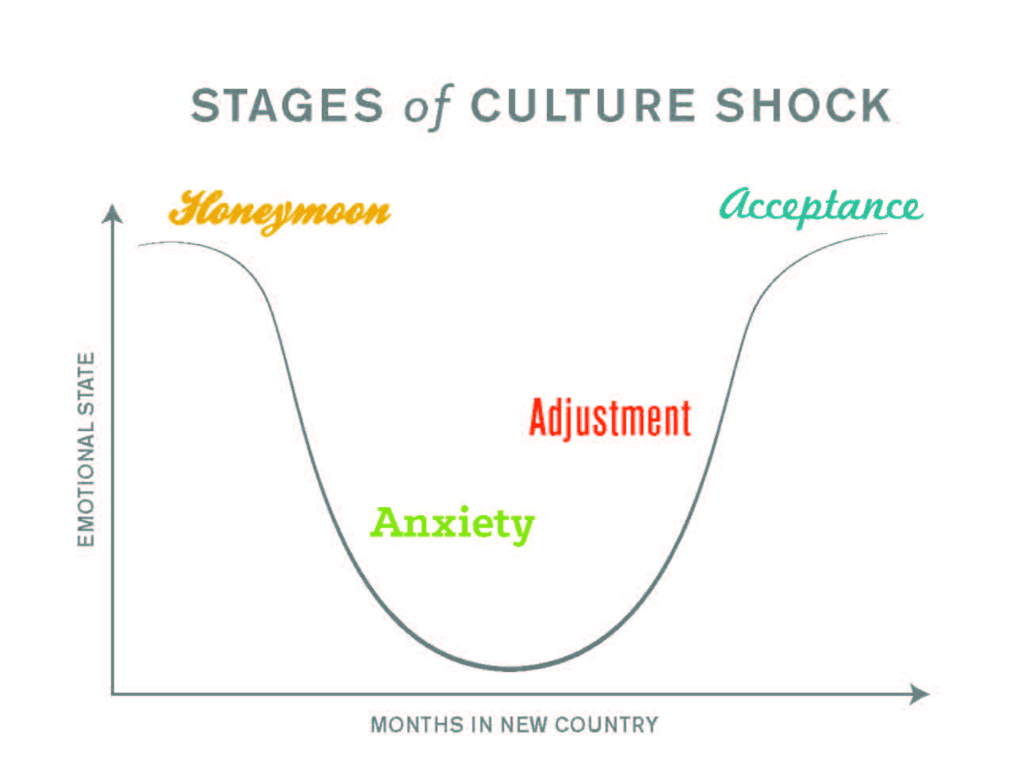

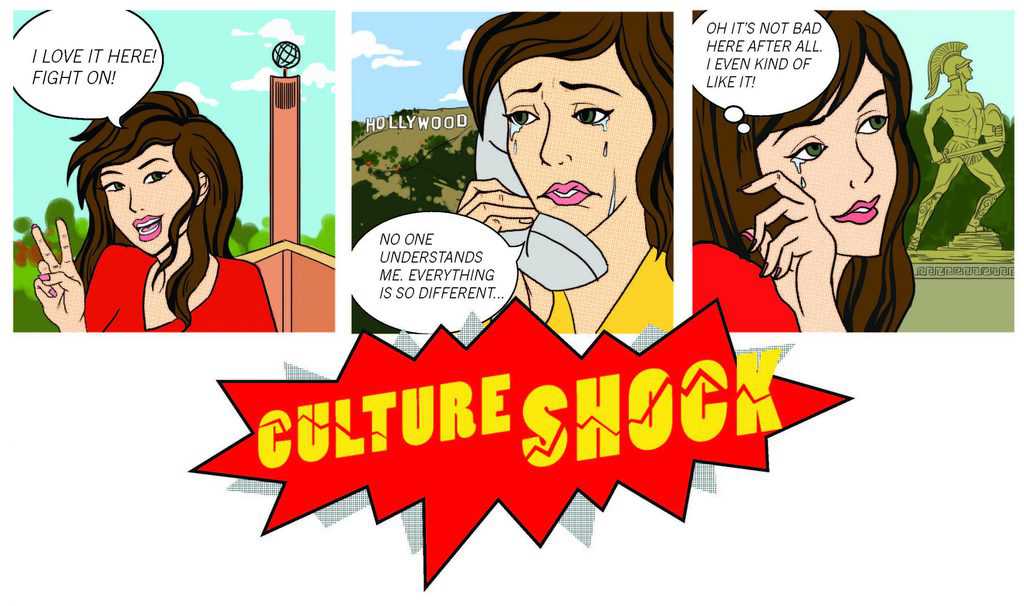

Culture Shock Stages

Many models of culture shock have been proposed since Canadian anthropologist Kalervo Oberg outlined his theory during a presentation to the Women’s Club of Rio de Janeiro in 1954. Oberg’s version encompassed four phases:

- Honeymoon: In this stage, the expatriate views the new surroundings with a tourist’s perspective. There is a sense of euphoria because everything is new and exciting.

2. Rejection: Oberg referred to this as the “crisis” stage. The expat begins to notice things in the new culture that don’t make sense. This disorientation leads to hostility toward the culture and its people, because nothing is the way it “should” be, and the expat feels confused and helpless.

3. Regression: Once the host culture is rejected, the expat reverts to the familiar comfort of the home culture, which is now seen through rose-coloured glasses. The expatriate complains constantly, and chooses to remain isolated from the host culture.

4. Recovery: Finally, the feelings of isolation begin to decrease. The expat feels more comfortable and in control of life in the new environment. With equilibrium restored, acceptance of the situation is now possible.

It is in the recovery stage that expats start to adjust and grow attached to their new culture.

“When you go on home leave you may even take things back with you,” Oberg said, “and if you leave for good, you generally miss the country and the people to whom you have become accustomed.”

Causes and Effects of Culture Shock

It’s easy to see how sudden immersion in a new culture can cause disequilibrium. People naturally use their own cultural norms as the point of reference for interpreting behaviours they encounter in other cultures, and are bewildered when their interpretations don’t fit.

Similarly, they are disturbed to discover that their own behaviours, which were received positively back home, result in negative feedback in the new environment.

The loss of the familiar cues that guided their interactions in their home culture leaves them feeling anxious, frustrated, and incompetent. Interpersonal communications, which were so effortless before, are suddenly fraught with uncertainty. Everything that was taken for granted is no longer valid.

Loss of identity is also an outcome of culture shock, since identity is inextricably tied to the values and experiences of the home culture. If what is valued back home holds no value in the new country, a crisis of identity can result, especially if a change in social roles or status is involved.

Being a stranger in a strange land has a way of forcing many expats to ask “who am I?” and “who do I want to be?”

Culture Shock is an Ongoing Condition, Not a Single Event

. In fact, as former expat Deborah Dundas pointed out during a phone interview, culture shock is more like a constant barrage of mini-shocks. Speaking of her seven years in Belfast, Dundas said, “it wasn’t the big things that caused culture shock – it was the details of everyday living.”

One of her first mini-shocks involved a typically mundane aspect of daily life: recycling. She was surprised – and somewhat unnerved – to find that the system of community recycling she was used to in her native Toronto didn’t exist in Belfast.

- What Is Aromatherapy Vs. What Are Essential Oils?

- What is La Tomatina in Bunol, Spain Like? What to Expect at the Famous Tomato Throwing Festival

“Every time I used a tin [in Belfast], I would carefully take off the label … and then would have no idea what to do with it,” she said. “It took me ages not to feel guilty about just tossing it in the garbage. But even then, I was still ripping off the labels, because I couldn’t help myself.”

The lack of familiar cultural cues caused Dundas to stumble many times as she attempted to navigate the social norms of her new environment. She questioned her own identity as she struggled to fit in. She passed through each of Oberg’s four stages in turn, and used multiple strategies to overcome culture shock.

Once she was able to adapt her behaviour to her cultural surroundings, Dundas began to feel comfortable in Belfast. She was finally able to relax and enjoy her life overseas. And yes, she eventually did stop stripping the labels off of tin cans.