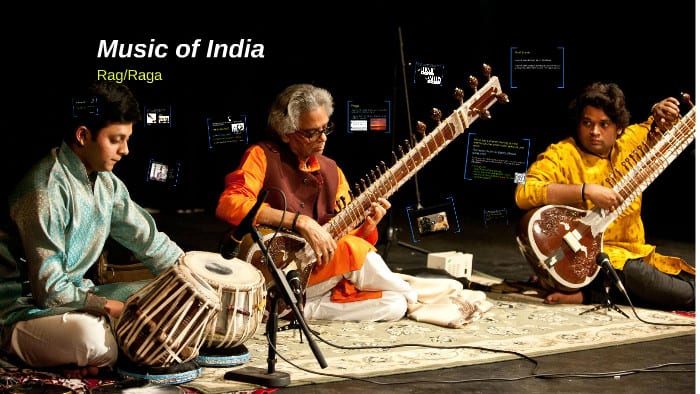

The traditions of Hindustani “classical” and regional “folk” music have existed side by side in India for several hundred years. In conjunction with cross-genre influences, several new genres have arisen. Dhun (sounds like dune) is one such example.

Sweet Folk Melodies

Mention of dhun in academic studies of Indian music are few and far between. It is most often treated only in passing, given a token mention in works that focus on the ‘classical’ tradition.

The explanations of dhun given in these works are often confusing and sometimes contradictory. The Gramophone Company of India gives the following definition:

“It represents a light tune, a mixture of sweet melodies, free from the disciplines of a raga. Usually played in a fast tempo and creates a mood of ecstasy.” (GCI 1982:Glossary).

Van der Meer refers to dhunas [dhuns] as “tunes of folk music”. He adds that “the material is often borrowed from classical music and can also be a source of classical music, but the aim of raga (a) delineation is absent.” (Van der Meer 1980:79).

Light Classical Music

Further difficulties arise when looking at the relationship between dhun melodies and rag. For instance Van der Meer writes that “Pahadi, originally a folk tune from the North, subsequently performed by classical musicians in a very light style known as dhuna … [is] now occasionally referred to as a raga. Yet this raga is never performed as a full fledged classical item.” (Ibid.:l75).

Neuman describes dhun as a “light classical song type” (Neuman 1980:272), He believes that the ‘classical’ artist performs dhun “to keep the less sophisticated listeners interested in classical music.” (Ibid.:l79).This suggests that dhun is more readily appreciated by the casual concert goer, being something he/she can identify with and enjoy.

Rags, Raginis and Dhuns

From the point of view of Indian ‘classical’ music theory, a dhun is not a rag yet the two concepts are intrinsically related. Radhika Mohan Maitra has written that when two ‘pure’ rags combine they create a new one which is called a ragini.

The combination of a rag and a ragini or two raginis gives rise to a third class of melodic type known as an uparag. A ‘pure’ rag expresses a single bhav (idea feeling), a ragini contains two such bhavs, while an uparag may express three or four bhavs. However;

“if we mix two uparags and if a fourth type of ‘rag’ and bhav arises, from the point of view of classi¬cal music this bhav can not be said to be a rag because it will lack a characteristic shape. Commonly, this type of ‘rag’ is referred to as a dhun, not a rag.” (Hamilton 1986:23)

This is do say that dhun does not have the specific melodic structure that a rag has. From the point of view of Classical music theory, a dhun appears to combine 4 or more classical rags and therefor can not be delineated according to notions of ascending and descending scale etc.

Source of Folk Music

Md. Amir Khan was of the opinion that “baul, bhatiyali etc. forms of folk and regional music evolved from dhun” (Ibid.:3). Though this comment is controversial, it underlines the view held in ‘classical’ theory which sees rag and dhun as existing on a continuum.

Many of the rags of Hindustani Classical music owe their identity to the melodies of the folk tradition. The latter tunes have been incorporated into former tradition and infuse it with a special vitality. Towards the end of a recital, a performer may choose to present a rendition of dhun.

Here the artist uses their expertise to elaborate on one or more melodies of “folk” origin. Part of the charm of this music is that it is not bound by the parameters of the classical tradition yet it often bears a resemblance to one or more classical rags. The high number of dhuns performed on recordings by ‘classical’ artists undoubtedly helps with the commercial marketing of classical music.