“I really enjoyed your article about the proposed Creek Indian reservation on our island. It is a shame that our local newspaper didn’t talk to you first before they wrote their article. Their article left out many historical details.”

“I have two questions, though. Your article’s description the architecture of the Creek Indians on the coast sounds just like our famous tabby architecture. Are you certain about this? I looked up “tabby” in several references. Other than in a blog someone wrote in Sweden referring to one of your books, all said that tabby architecture was introduced by the Spanish and was originally the word, “tapia.” This is what I tell all my clients when showing tabby houses.

Also, you called the Indians on the South Atlantic Coast, the Wahale. All the references, including the New Georgia Encyclopedia, called them the Guale. The encyclopedia article was written by an anthropology professor at the University of Georgia. I would think that he knew what he was talking about”.

Response to the reader’s questions

The understanding of North America’s past is constantly changing. What might be the truth, today, might not be truth tomorrow. Until 2007 I would have also said that tabby architecture was introduced by the early Spanish colonists. This is what I was taught in college and this is what most references state today.

Guale is the Medieval Castilian way of writing the English phonetic sound, wah-le, which is how the Spanish “heard” the Creek word “wahale.” The 15 languages of Spain and Portugal did not originally have the letter “w” in their alphabets. Southeastern anthropology students are now being encouraged to learn the Muskogean languages so that they can better interpret the sites associated with the mound-building cultures of the region.

Tabby or tapia is a primitive form of concrete construction that was frequently utilized on the South Atlantic Coast by Spanish and English colonists. In this type of construction, wooden boards were first erected in the form of the building’s walls. Boards were also used to encase window and door openings. A liquid mixture of crushed seashells (or limestone flakes,) sand, clay and crude hydrated lime made by burning sea shells was poured into the forms.

It could take several months for the solid walls to fully cure, because they were typically 16 to 24 inches thick. The wall forms were filled with the concrete a few feet at a time in order tamp the mixture down and remove air pockets. The hydrated lime made from burned shells or limestone changes chemically as it dehydrates (releases water) in the curing process. The mixture evolves into a manmade limestone.

Once hardened, tabby walls were as strong as stone and fully fireproof. The floors and roofs of European Tabby houses were constructed of wood. For this reason, the ruins of many tabby walls survive in coastal areas long after the wooden architecture has turned to saw dust or ashes.

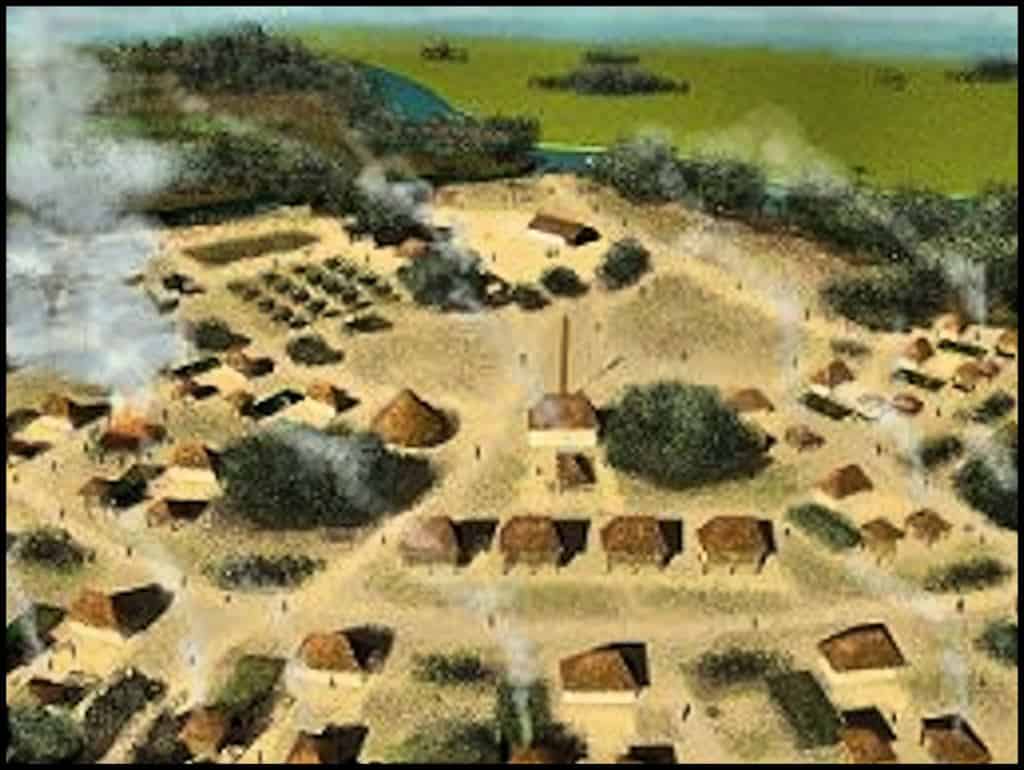

The oldest known use of tabby construction dates from at least 750 AD in the northern part of the Mexican State of Vera Cruz. This area was occupied by the Totonac People whose word for house, chiki, is the same as the Hitchiti-Creek Indian word for house. The Totonacs built multi-story houses for their elite and temples, whose walls and floors were solid tabby. The walls and floors were temporarily braced by logs until the primitive concrete had hardened sufficiently to be self-supporting.

Early Spanish and English archives tell a different story

In 2007 I was retained to prepare precise three dimensional architectural drawings of the buildings discovered by archaeologists of the American Museum of Natural History while working on Cumberland Island, GA. They had discovered the Mission Santa Catalina de Guale, plus numerous Native American structures. Preparation for the work included research into all available Spanish colonial archives.

A Spanish army officer, who was evidently an architect or engineer, was making inspections of new construction projects along the South Atlantic Coast in 1567. He described the appearance of Natives’ buildings in Guale (Wahale) as beautiful edifices that “glistened like pearls.” The officer went into detail of how they were constructed. First, a prefabricated framework of saplings was erected. This was in-filled with a basket-like mesh of canes, palmetto fronds or marsh grass.

Local clay was packed around the mesh. The buildings were finished with stucco, composed of white kaolin clay (imported from about 140 miles upstream on the Altamaha River,) white sand, crude lime made by burning shells and crushed shells. The finish coat hardened to form a protective membrane that prevented the driving rains of tropical storms from destroying the vulnerable inner core of dry clay and saplings.

The archaeologists of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology have found that the buildings of the first capital of the Spanish Province of La Florida at Santa Elena (Parris Island, SC) were built in an identical manner to those indigenous structures described by the Spanish officer. Santa Elena was occupied from 1566 till 1587.

Surviving Spanish tapia or tabby buildings and ruins date from a period when their architects and fortification engineers were already utilizing a natural shell-based concrete called coquina stone to build important structures such the last version of Castillo San Marcos. Evidently, the Spanish figured out in the late 1600s or early 1700s that walls constructed entirely out of the mixture of sand, lime, shells and clay would cure into structures that were similar in strength to coquina stone.

Did other Native Americans build structures with crushed shell stucco?

American Indians living on the South Atlantic Coast had infinite supplies of sea shells to use in their architecture. Currently, it is believed that the use of crude lime stucco made from shells was concentrated in the areas occupied by the Wahale (Guale.) Apparently, their cousins living upstream on the Altamaha River, the Tamatli, also applied white, shell-based stucco to at least some of their buildings. The Tamatli and their major towns of Tama and Altamaha were visited by the de Soto Expedition in the spring of 1541. The chroniclers of the de Soto and Pardo Expeditions also mentioned temples and houses finished in white stucco in several other towns, but these may have been finished with white clay, without shell and hydrated lime reinforcing.

Native Americans began tempering pottery vessels with crushed shells at least as early as 750 AD. The shells caused a chemical change, which allowed pottery to be fired at a much lower temperature. It is quite likely that some indigenous cultures experimented with applications of the crushed shell-clay mixture to buildings. It is known that Southeastern Indians coated their temples and pyramidal mounds with brightly colored clay stuccos. These stuccos are seldom, if ever, tested chemically by archaeologists. They may contain hydrated lime made from burning shells.

The book, Tellico Archaeology by Tennessee archaeologist, Jefferson Chapman has an interesting chapter that was derived from the Memoirs of Lt, Henry Timberlake. At the time the book was written, North Carolina and Tennessee archaeologists focused on recent Cherokee history, and did not learn the languages and cultural traditions, of the peoples who originally occupied these regions. Translation of some Creek Indian words in Timberlake’s memoirs results in a much more detailed understanding of the Southeast’s pre-European history.

Lt. Timberlake was a Virginia militia officer, who journeyed into the Overhill Cherokee towns on the Little Tennessee River to consummate a peace agreement in November of 1761. Timberlake spent several weeks in the Cherokee town of Tamatly. He recorded many of the customs observed there and drew their buildings. The chief of the Tamataly Cherokees used the Hitchiti-Creek and Maya word, mako, for his title, which means “great leader” in both languages.

Timberlake recorded his name as Ostamaco, which means “fourth chief” iin the Hitchiti-Creek language. Contemporary books give the man’s name as Ostaneca, but this seems to be an attempt to create a name that is similar to an abreviation of some Cherokee words, Why would a famous Cherokee chief use a Maya-Creek title? The answer is related to his town’s architecture.

Timberlake stated that the Tamatly houses were large rectangular structures with three rooms. He used the exact words of the Spanish officer in the 1500s, while describing the houses as white stucco mixed with crushed freshwater mussel shells, which caused the houses “to glisten like pearls.” The Cherokee Tamatly houses of 1762 were identical in every detail to the missionary’s and chief’s houses at Mission Santa Catalina de Guale built by Wahale-Creek Indians on the coast of Georgia around 1600.

Tamatly is obviously an English way of writing Tamatli, which was the powerful province visited by Hernando de Soto in the early spring of 1541, while he was passing through southeast Georgia. Further research located the homeland of the Highland Tamatli in a beautiful valley between Murphy, NC and Andrews, NC. Apparently, the Tamatli established very large colonies in the mountains of North Carolina, and also around Tamasse, SC on the Keowee River.

There were once 24 mounds in the Andrews Valley, but most have been bull-dozed in the past two decades by real estate speculators. The largest Highland Tamatli mound still is visible from a four lane highway in Tomatla, NC. Apparently, these Creeks were either conquered or absorbed by the Cherokees in the early 1700s, and from then on, became increasingly Cherokee in culture. In 1763 the Tamatli were still mixing Creek words with Cherokee words in their dialect, but by the 1830s were speaking a Cherokee dialect similar to what is spoken in Oklahoma today. It is almost certain that early examples of tabby stucco lay hidden under the fertile landscape between Murphy and Andrews, NC.