Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who crucified Jesus, is known for one of the famous questions in all of history: “What is truth”?

If the New Testament Gospel manuscripts are any indication, Jesus had supplied that answer repeatedly during his ministry. “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life,” Jesus had declared to his disciples (John 14:6), and his entire ministry, in fact, was committed to a purpose that presumed his authority to define and proclaim it.

Christianity vs Relativism

Jesus’ claims to certainty and absolute authority contrast with the prevailing mainstream culture today, which increasingly eschews claims of certitude in connection with religion and morality.

As the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche famously declared: “You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist.”

Of course, without moral certainty, society has little in the way of an external, substantive basis to judge child molesters, rapists, identity thieves, or greedy corporate embezzlers. We are instead left with conflicting and ambiguous standards of utility and tolerance.

But this itself is somewhat of a utilitarian argument for “Truth.” And it has done little to bring the masses around.

Relativism Examined

According to the Internet Encylopedia of Philosophy, relativism asserts that a conceptual thing (belief, value, beauty, etc.) is “relative to some particular framework or standpoint” and that no such standpoint or framework is “uniquely privileged” over another.

This, of course, puts Jesus Christ and his followers on a collision course with relativists.

Indications are, however, that the relativists are winning in today’s culture wars. In fact, relativism is making inroads with those who otherwise claim to be “Christian.”

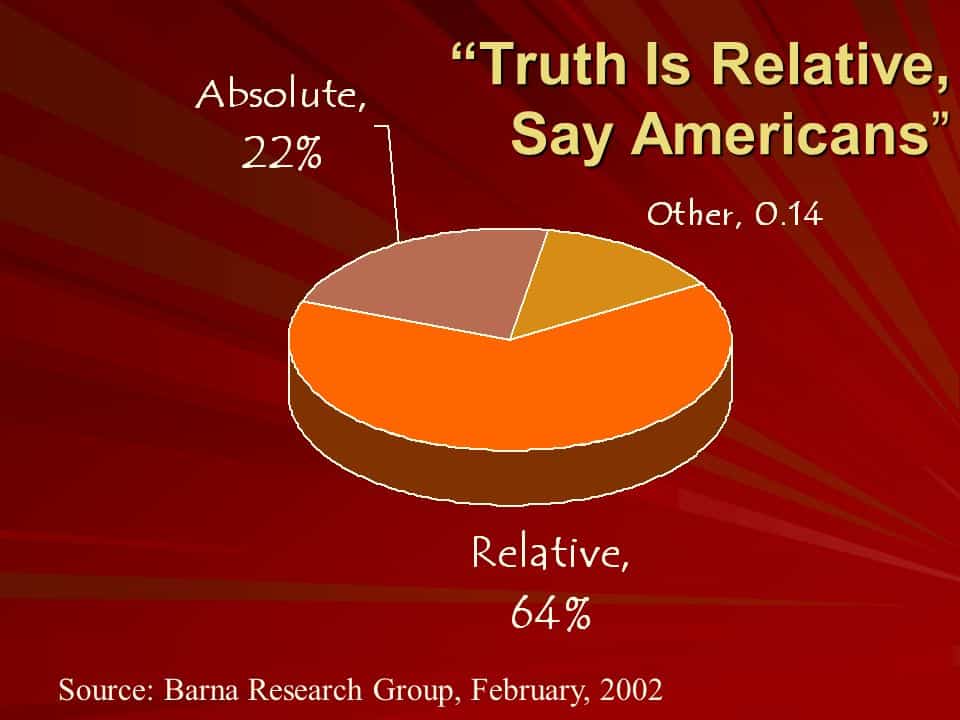

According to the Barna Research Group, a 2002 survey showed that approximately 64% of American adults believe truth is relative to one’s circumstances or situation. Only a third of the respondents cited agreement with the concept of “absolute truth.” According to Barna, these numbers include self-described Christians.

Popular though it may be, relativism, as well as skepticism, falls short in credibly confronting some fundamental challenges to its philosophical integrity. The most powerful challenge stems from life itself. Quite simply, relativism cannot be logically lived out.

“An individual will live his or her life almost entirely on a nonrelativistic true-false basis,” writes Winfried Corduan, a religion and philosophy professor at Indiana’s Taylor University. “Either I missed the bus, or I didn’t miss the bus. Either this is Friday, or it is not Friday. Either I have eaten lunch, or I have not eaten lunch.”

No sane person approaches life in a purely relativistic sense. If you apply for a job, you will either be hired or you won’t.

If you get the word that the job went to someone else, and yet show up for the job, expecting an office and a paycheck, what do you think will happen? When your would-be boss reminds you that the job went to another candidate, are you going to say: “Well, that’s your truth. My reality is somewhat different.”

As Professor Corduan observes, “Relativism only seems to pop up at certain crucial moments, usually in the sphere of morality and religion.”

The Real Challenge to Knowing Truth

It’s one thing to disprove relativism, but it’s another to prove Christianity. And this is where skepticism comes into play.

Closely related to relativism, philosophical skepticism is a school of thought that critically questions whether one can ever really possess true knowledge.

While many skeptics believe that some knowledge can be reached, for most, the quest for truth and knowledge is a never-ending one – and a very personal one. Skeptics thus contend that anyone making exclusive, universal truth claims (as Christians do) should be considered suspect.

Here, a distinction is necessary. A true skeptic is one who argues that truth and knowledge, in their purest and fullest sense, are forever elusive. This is not the same as one who suspends judgment temporarily until further information becomes available.

Of course, suspension of judgment is often indefinite in our society, given the degree of apathy we see around us. Apathy is perhaps the greatest challenge, not only for Christianity but other religions as well. It was no different in the Roman world, when the emperors used entertainment to appease and distract the people, while they continued in their corrupt and tyrannical ways.

The significant thing about Pilate’s question is that, according to the Gospel of John, he didn’t stick around to hear an answer. And this is the case with most people today. They glide through life, refusing to confront truth claims generally, let alone those of Christianity, preferring ignorance to knowledge.

Is it because they are afraid of what they might uncover?